Flavio Favelli

FLAVIO FAVELLI

FAMI MALE

a cura di

NEVE MAZZOLENI

INAUGURAZIONE

GIOVEDI 29 GIUGNO 2017

ORE 18-21

dal 29 Giugno al 21 Settembre 2017 solo su appuntamento

Neve Mazzoleni: Hai una capacità rara nel cercare, soffermarti sul dettaglio dimenticato, raccogliendolo e riattivando intorno ad esso un significato e una storia spesso a sfondo personale, comunque profondamente umana. Cosa ti ha portato alla Stazione Marittima di Messina? Flavio Favelli: In estate vado spesso in Calabria, ma non per andare al mare, per andare in bassi Itaglia come si dice in Emilia. L’anno scorso ero a Reggio Calabria, sullo stretto, uno dei pochi luoghi che sento esotico, un po’ come andare a Baghdad. Sono andato per vedere e vivere certi contrasti, certi paesaggi poco ortodossi, certe insegne di negozi, certi incarti di pasticceria… ma soprattutto per tutte le cose abbandonate, rotte, sbragate, cadenti con le loro macerie, come certi palazzi delle città vecchie insieme a quel poco di natura che riesce a crescerci dentro che crea una magnificenza semi artificiale. Amo la desolazione, quel degrado a tinte nobili che trovo solo nel Meridione. Sono visioni di un passato consunto, quelle che il Nord non si può più permettere, situazioni sconcertanti, una parte di mondo sfasciato che permette spettacoli sublimi, fra il pittoresco e l’orrido, il catastrofico e l’apocalittico, perché l’apocalisse è bellissima quando si è solo spettatori. Una mattina ho preso l’aliscafo e sono andato a prendere un caffè a Messina. Sono stato colpito dalla stazione di Messina Marittima: una bellissima architettura fascista semideserta a pochi metri da Messina Centrale. L’edificio è ad arco con un enorme muro in travertino con un camminamento sopraelevato che attraversa i binari. Sembrava un quadro metafisico con la parete avorio altissima. Anche se c’era rumore – traghetti, treni, auto, annunci lontani – c’era un silenzio di fondo. Ho visto, ritmate, delle scritte esili a matita blu, dei versi gracili che si svolgevano lungo il muro. In un luogo solitario, immobile rispetto al flusso del presente, intercetti una scritta ripetuta, fragile, diversa da un marchio, unica. Perché ti è piaciuta? Prima per il suo ordine, il suo aspetto formale composto, leggero, appena percettibile e poi il significato, sconcio, sguaiato e sensuale allo stesso momento. Oltre alla sua dolcezza: so baciare… so fare l’amore, fami male. La cultura dominante la bollerebbe come volgare e scurrile. La volgarità è un abisso complesso da cui si tengono alla larga solo gli stolti e gli ignoranti oltre a quelli che aspirano alla santità e ai seguaci del sacro. Sono 11 stazioni di una via crucis misterica dove si intrecciano talmente tanti termini, molti inventati, che solo a pronunciarli evocano immagini molteplici… assomiglia ad una nenia che inizia sempre allo stesso modo – cerco - una specie di rito – preghiera nella speranza di trovare un giovinetto rigorosamente di 20-19 anni. Come arriva nella tua pratica? La mia pratica coincide con tutto ciò che mi piace e tutto quello che piace ad un artista è per sua natura articolato, complesso e ambiguo. Mi piacciono le scritte, i termini sboccati e quelle che il costume chiama le cose spinte, perché se non si spinge si sta fermi. Forse peccato solo che quel giorno non fosse sabato. Una forma di epigrafia contemporanea, legata al tuo bagaglio di storico, dove ti sei preso la briga di catturare la scritta dal travertino e studiarla. Da lì hai fantasticato su chi possa esserne l’autore. Leggendo questa via crucis avvengono tante cose: immagini, pulsioni, processi onomatopeici, ricordi. Parole masticate, sbocconcellate, impastate da stati tanto poveri e grezzi quanto ebbri e dionisiaci. Un beracazo: un bel ragazzo o un bel cazzo? Sofre lamore: so fare l’amore o soffre l’amore? So baciare: già, so baciare? È molto probabilmente una persona di sesso maschile o multiplo o forse è solo una persona di sesso e basta che cerca beracazi. Faceva caldissimo con una luce abbagliante. Von Gloeden non fotografava i ragazzi da queste parti a Taormina che è poco più giù? Tu dici “Amo la desolazione, quel degrado a tinte nobili che trovo solo nel Meridione”. Contrasti e stratificazioni. La malinconia gioca un ruolo nella tua ricerca. Fra Scilla e Cariddi in uno dei luoghi più densi del pianeta dove si intreccia non la nostra storia, ma la storia del mondo su un bellissimo edificio fatto dal fascismo ma lercio e offeso da tag indifferenziate, quasi abbandonato, in una desolazione assordante e un degrado concreto, ho trovato questi messaggi intensi e letterari. Tutto ciò, visto il contesto, il clima e gli odori – non c’è quello di zagara, ma ancora quello della ferrovia con le traversine ancora vergini dalla TAV – è commovente, è tragico nel senso di sublime. È una grande opera complessa. Mi hai raccontato dei tuoi viaggi da bambino, abitudine che non hai perso. Ho ancora una bellissima foto di quando ero bambino avrò avuto 7 anni con un arancino (o arancina) e una bottiglietta in vetro di Chinotto Levissima sul traghetto sullo Stretto. Mi ricordo questi viaggi con mia madre; a volte penso che mia madre al di là per la passione del Bello e dell’Arte, mi abbia – a volte forzatamente – portato a fare viaggi perché alcune cose bisognava vederle e viverle, come una specie di compito. E il Meridione andava visto, si doveva vivere il più possibile perché era la Bellezza vera, senza mediazioni. Perché portare questo intervento proprio in The Open Box? È da quando ho visto queste scritte, che voglio in qualche modo presentarle; questa è stata l’occasione. Delle 11 stazioni ne ricopierò tre sui tre muri di The Open Box.

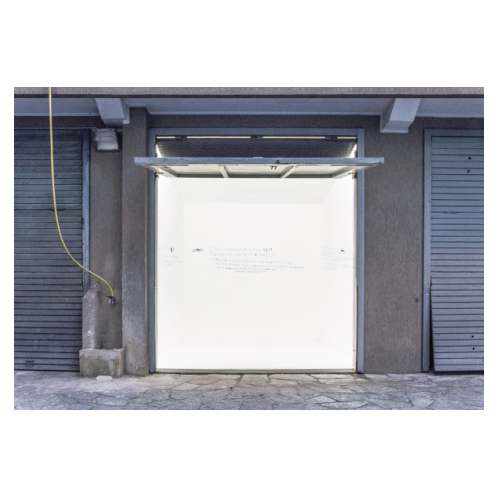

Fami male, 2017, matita colorata su muro

flaviofavelli.com

THE OPEN BOX

Via G.B. Pergolesi 6

20124

MILANO

www.theopenbox.org

info.theopenbox.org@gmail.com

+393382632596

FLAVIO FAVELLI

FAMI MALE

curated by

NEVE MAZZOLENI

OPENING

THURSDAY 29 JUNE 2017

6-9 PM

from 29 June to 21 September 2017 by appointment only

Neve Mazzoleni: You have a rare capacity for seeking out and lingering over the forgotten detail, treasuring it and reactivating around it a meaning and a story often with a personal and in any case profoundly human background. What took you to the Stazione Marittima in Messina? Flavio Favelli: I often go to Calabria in the summer, not for the seaside, but to go to bassi Itaglia as Southern Italy is somewhat vulgarly known in Emilia. Last year I was in Reggio Calabria, on the strait, one of the few places I feel to be exotic, a bit like going to Baghdad. I went to see and to experience certain contrasts, certain somewhat unorthodox landscapes, certain shop signs, certain pasticceria wrappings… but above all for all the abandoned, broken, ragged things, crumbling into ruins like certain buildings in the old towns together with what little that is natural that manages to grow in them to create a semi-artificial magnificence. I love the desolation, that noble decadence I only find in the South. These are visions of a threadbare past, those which the North can no longer afford, bewildering situations, a broken part of the world that permits sublime spectacles, ranging from the picturesque to the horrible, the catastrophic and the apocalyptic, because the apocalypse is beautiful when you are just spectators. One morning I took the hydrofoil and went for a coffee in Messina. I was struck by the Messina Marittima station: beautiful, semi-deserted Fascist architecture just metres from Messina Centrale. The building is arched with an enormous wall in travertine featuring a high-level walkway crossing the tracks. It looked like a metaphysical painting with that soaring ivory wall. Even though there was noise – ferries, trains, cars, distant announcements – there was an underlying silence. I saw thin, rhythmic writings in blue crayon, graceful verse running along the wall. In a solitary place, immobile with respect to the flow of the present, you intercepted a repeated, fragile script, different from a mark, unique. Why did you like it? Firstly for its order, its composed, light, barely perceptible formal aspect and then for its meaning, dirty, vulgar and sensual all at the same time. As well as for its sweetness: so baciare… so fare l’amore, fami male (“I know how to kiss… how to make love, hurt me”). The dominant culture would label it as tasteless and smutty. Vulgarity is a complex abyss ignored only by the stupid and the ignorant along with those who aspire to sanctity and the followers of the sacred. There are 11 stations on a mystic via crucis in which so many terms are entwined, many of them invented, they need to be pronounced to evoke multiple images… It is like a lullaby that always begins in the same way – I’m looking for it – a kind of ritual-cum-prayer in the hope of finding a young man of no more than 19-20 years old. How did it arrive in your practice? My practice coincides with everything I like and everything an artist likes is by its very nature articulated, complex and ambiguous. I like the writings, the filthy terms and those that public decency would see as hard core, because if you don’t push you stand still. Perhaps it’s just a shame that that day wasn’t a Saturday. A form of contemporary epigraphy, tied up with your historian’s baggage, in which you have taken the trouble to physically capture the script on the travertine and study it. From there you’ve pondered on whom the author may be. Reading this via crucis provokes many things: images, pulses, onomatopoeic processes, memories. Chewed up, mangled words, kneaded by states as poor and rough as they are inebriated and Dionysiac. A beracazo: a “bel ragazzo” or “beautiful boy” or a “bel cazzo” or “fine cock”? Sofre lamore: “so fare l’amore”, “I know how to make love” or “soffre l’amore”, “suffers love”? So baciare: right, “so baciare”, “do I know how to kiss”? Very probably the author is of the male or multiple sex or perhaps just a person of sex looking for beracazi. It was baking hot with a dazzling light. Didn’t Von Gloeden photograph the boys from around here at Taormina, just a little further down? Your say “I love the desolation, that noble decadence I only find in the South”. Contrasts and stratifications. Melancholy plays a role in your research. Between Scylla and Charybdis in one of the densest places on the planet where it is not our story that is woven but the story of the world in the form of a beautiful building constructed by the Fascists and now filthy and insulted by indiscriminate tags, almost abandoned, in a deafening desolation and all too real decay, I found these intense and literary messages. However, given the context, the climate and the odours – not that of orange blossom but there is still that of the railway with the still virgin sleepers of the TAV – it’s moving, it’s tragic in the sense of sublime. It’s a great and complex work. You have told me about your trips as a child, a habit you have never lost. I’ve still got a beautiful photo of when I was a child; I would have been 7 years old with an arancino (or arancina) and a glass bottle of Chinotto Levissima on the ferry over the strait. I remember these trips with my mother; at times I think that apart form a passion for the beautiful and for art, she took me - by force at times – on trips because some things had to be seen and to be experienced, as a kind of assignment. And the South was to be seen; one had to experience as much as possible because it was true beauty, without mediation. Why have you brought this project in particular to The Open Box? Ever since I saw these writings I've wanted to present them in some way; this was an opportunity. Of the 11 stations I’ll be copying three on the walls of The Open Box.

Fami male, 2017, coloured pencil on wall

flaviofavelli.com

THE OPEN BOX

Via G.B. Pergolesi 6

20124

MILANO

www.theopenbox.org

info.theopenbox.org@gmail.com

+393382632596